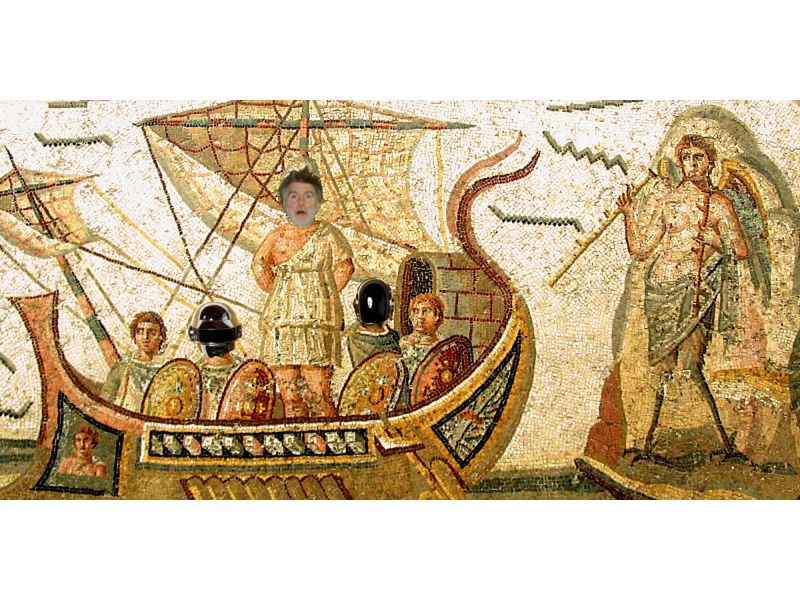

Sometime around the 7th or 8th century BCE, history tells us that a blind poet named Homer composed a story that would come to be called the Odyssey. It’s an epic poem that tells the story of the ruler of Ithaca, Odysseus, and his journey back home after fighting in the Trojan War. In all, Odysseus’s war and journey back took 20 years. The Odyssey, despite its length, was an engaging story to the Greeks, so it was passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition, and at some point in time, it was written down and has made it to the modern-day.

So what exactly makes the Odyssey an epic poem? Masterclass has an article that mentions typical characteristics of the genre. These include having a powerful, brave hero, omniscient and third-person narration, a journey across a variety of settings and terrains, otherworldly and even supernatural obstacles that challenge the hero with insurmountable odds, an invocation to a muse that provides guidance to the speaker, and a formal writing style. To its credit, the Odyssey follows this list with few exceptions.

Sometime around 2015, I was forced to read a translation of the Odyssey in my first year of high school. In the 2,800-ish years between its initial oral performance and my reading, someone got the bright idea to recite a poem while music was playing in the background. A while after that, someone else figured out how to make electricity do math for them. Then, someone else made that electric-math-thingy, which they called a computer, make bleep bloop noises, and a little after that, James Murphy founded a band called LCD Soundsystem. In 2007, they released “All My Friends” on the album Sound of Silver.

More than two millennia after the Odyssey, James Murphy accidentally wrote an epic poem. While I could go through the list and draw parallels, it can sometimes be a stretch—it’s hard to find a clear-cut example of an artistic muse in “All My Friends,” for instance. But LCD Soundsystem’s epic poem is one that’s adapted to the modern age, one that connects with its listeners in an intimate way that the Odyssey cannot. Gone are the times where heroes must have bravery and resolve. The Modernists threw out the concept of formality 150 years ago.

To make a work an epic, we need a hero, and in “All My Friends,” this is James Murphy. Murphy is a normal man, which may seem counterintuitive, as he doesn’t have many of the qualities of a traditional hero. However, there is some precedent for breaking this rule. Leopold Bloom, another normal man, is the protagonist and Odysseus stand-in from James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is heavily based on the Odyssey. In addition, Murphy’s normalcy supports the main theme of the song—growing old—better than a traditional epic hero ever could.

Murphy’s adventure is his life. “All My Friends” tells the story of a party thrown one night, which Murphy states “could be the last time” something like this happens as his age catches up to him. He wants to feel young again. But it’s not just that he’s throwing this last hurrah; as he attempts to not think about aging, he reflects upon his past. He mentions that “if the sun comes up and I don’t still want to stagger home/then it’s the memory of our betters/that are keeping us on our feet.” His memories of earlier days, of “blowing eighty-five days in the middle of France” are what’s fueling him through the night.

The list mentions that an epic often features otherworldly or supernatural obstacles, with our hero facing almost insurmountable odds. But “All My Friends” is blatantly modern. Getting old is insurmountable—it happens to everyone. Murphy’s last wild party is down-to-earth and realistic, a story about getting older that can connect to the audience on a more personal level.

Even the rhythm of the song ties into the idea of being relatable. The pounding piano riff contains exactly two notes and does not change for the entire seven-and-a-half minute runtime, eventually becoming a monotonous drone. In a way, the riff becomes a representation of life itself: initially uptempo and exciting as all hell, but as it goes on, it becomes the most boring thing you’ve ever heard. The riff’s little imperfections only make it better, and I don’t think I need to explain what little imperfections symbolize in a riff that acts as a metaphor for life.

One other thing the epic poem checklist mentions is the idea of an omniscient narrator. Although James Murphy certainly isn’t omniscient, his age gives him the experience he needs. Murphy may not know what’s going to happen in the future, but he can talk about the past in an omniscient fashion with his accumulated knowledge. It’s this omniscient introspection into his past that brings the theme of growing old to the forefront of the song. Murphy quips “When you’re drunk and the kids look impossibly tanned/you think over and over, ‘Hey, I’m finally dead,’” and then all of the sudden, the realization sinks in, and his world changes. He’s old, out of touch, burned out, and he is not one of “the kids” anymore. But this is a realization Murphy can only make in retrospection. His younger self would have never thought about where he might be now.

That thought is a little scary, given how much effort Murphy put into making his story and lyrics relatable to the audience. “All My Friends” subconsciously pokes at the listener and makes them acknowledge the fact that nobody can be invincible forever, that everyone will have this last hurrah. The goal is simply to live such that you “wouldn’t trade one stupid decision/for another five years of life.” Murphy expresses the entire ride better than I can: “You spend the first five years trying to get with the plan/and the next five years trying to be with your friends again,” then “you drop the first ten years just as fast as you can/and the next ten people that are trying to be polite,” then hits you with the incredible, frightening “Where are your friends tonight?”

After a final refrain of “If I could see all my friends tonight,” the song ends—Murphy does not provide a happy ending. Over the course of the track, he takes you on a journey through the night and ends with an existential crisis. But the Odyssey doesn’t end happily, either. Sure, Odysseus is home after 20 years of war and travel, reunited with his wife Penelope, his son Telemachus and his father Laertes. But at what cost? Many of his companions died in the Trojan War and all of his men died on the way back home. He killed 108 suitors who were fighting over his wife. Where are his friends tonight? As it turns out, even Odysseus can’t fight growing old.